Could we say something new about gun deaths and bring hope? A reporter's notebook

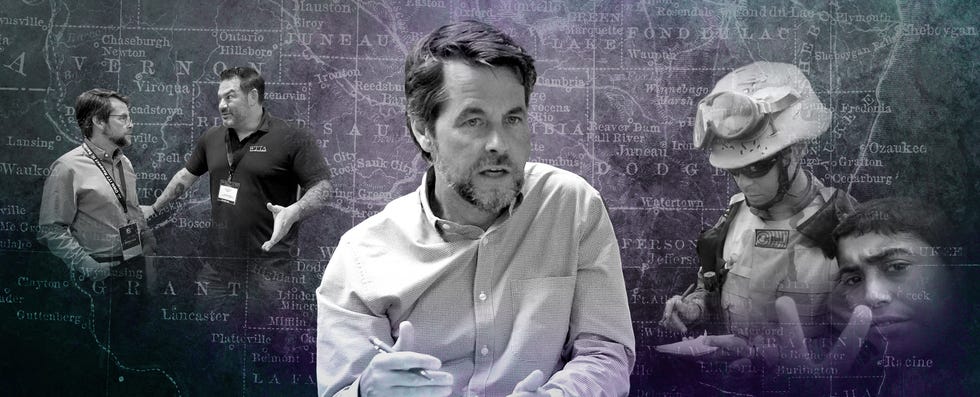

John Diedrich

John DiedrichIf you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, call or text the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text “HOPELINE” to the National Crisis Text Line at 741741.

It wasn’t my idea to do a project on gun deaths in Wisconsin.

In 2021, George Stanley, then-editor of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, suggested taking a deep look at firearms deaths in Wisconsin, not just the ones that usually make the news.

I was a little skeptical at first. Guns are among the most heavily covered, scrutinized subjects in our country. What could we say that hadn't already been said?

A longtime gun owner, George was persuasive. If we could get data that hadn’t been gotten, talk to everyday gun owners about their practices, and keep the focus on Wisconsin, we could tell readers in our state something they didn’t know – and maybe even help save some lives along the way.

My first questions were: Could we get the data? And would gun owners talk with me?

Homicides are horrible, and there are other gun deaths too

I’m not a gun owner (to answer a question I got that question repeatedly on this project). But I have written about firearms quite a bit over the years and fired guns at shooting ranges as part of my job.

In a previous position, I covered troops from Fort Carson in Colorado Springs and was embedded with the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment in Iraq in 2003. A year later, I returned home to Wisconsin, and my beat became the Milwaukee Police Department and crime. Five years later, I wrote about a troubled gun shop, Badger Guns. And in 2013, I was part of a team that uncovered a botched federal gun-buying sting in Milwaukee.

For this project, I went on the O’Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University, where reporters can dig into an issue for months, teaming up with students and tapping the university’s resources and expertise.

The editor on this project is Greg Borowski, who has shepherded, in some role, every major piece of journalism the Journal Sentinel has done in the past 15 years. After George retired, Greg moved up to be editor and remained on this project.

An early call went to Milwaukee County District Attorney John Chisholm. He grew up with guns and is more knowledgeable than most cops. He was leading the gun unit in the prosecutor's office when I first started at the Journal Sentinel.

Chisholm knew about best practices when handling firearms and was alarmed by the recklessness he was seeing, resulting in a historic level of gun homicides. Part of that was simply a numbers issue, Chisholm said.

“Everyone who wants a gun now has one – and even some people who don’t,” Chisholm told me last summer.

I also spoke with Mallory O'Brien, a researcher I knew from her days as head of the Homicide Review Commission in Milwaukee. Now working at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, O'Brien had delved deeply into gun deaths. She observed a gun has a very long lifespan and as more guns come into the picture, the landscape is changing long-term.

I also interviewed Milwaukee Police Chief Jeffrey Norman. I met Norman when he was a detective. As chief, he told me how his people are grappling with gun deaths, which soared in the pandemic, and how the job of policing has changed as more people are carrying guns since Wisconsin legalized concealed carry in 2011.

For decades, fellow reporters and I have covered the despair from the scourge of fatal shootings that plague parts of Milwaukee, along with accidental discharges and police shootings. These are the cases that come to Norman and Chisholm and the people they supervise.

Those were terrible – but I knew there were more. The full picture seemed like it should include suicides.

I reached out to Jeff Blair, a former Army intelligence officer I knew from my days covering the military. He told me, "Part of the problem is the media highlights the unusual and suppresses the usual."

And that tends to give people a distorted view of the world.

I felt a little defensive at first over the long-standing media practice of not reporting suicide. It was out of a real concern of triggering other suicides. And yet I paused and admitted: He was right about the distorted view.

That sent me to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. After a battle, they refused our request for a massive and thorough set of data, one they routinely let academic researchers use. So O’Brien student assistants Alex Rivera Grant and Ben Schultz and I set out to get the data from the counties.

We thought we would be lucky to get 25 of the state's 72 counties. Thanks to the efforts of attorneys Tom Curley and Tom Kamenick, the number pushed to 71. It is the most complete look at the data and this issue to date.

Some coroners and medical examiners were skeptical of our project at first, feeling like it had an anti-gun angle. As I talked to them and explained the approach, their tone changed. I learned many of them are overworked and underpaid, yet they were extremely helpful for our project.

Then I started dialing experts on gun deaths. Many gave me the same lines that I heard – some literally word-for-word – over the years.

Then I talked to John Roman, director of the Center on Public Safety and Justice at the University of Chicago. He said something I hadn’t heard.

“I'm gonna get my liberal progressive card pulled for saying some of these things, but that's OK,” Roman said. "What's interesting, what never gets taught, is how many people buy a gun, and then nothing happens. It doesn't go off accidentally. It's not used in a suicide. It doesn't get lost or stolen or sold and becomes a crime gun. Hundreds of millions of guns fit into that category, and I'm really interested in what we can learn about that, to help us improve public safety in a gun-owning world. What are these people doing?"

What is not happening? And given how many guns are in circulation, maybe it is surprising more tragic deaths are not happening.

I had to find those everyday gun owners and learn more.

My editor had recommended the book “Talking to Strangers” by Malcolm Gladwell. And this is what I felt like I was trying to do, talk to strangers. I mean, that is what we do as reporters.

I found the first people willing to talk at the Daniel Boone Conservation League in Hubertus. Through Boone, I met Jeff Pharris, a firearms instructor who was very generous with his time.

From there, more gun owners came. A few turned to a dozen, and then dozens.

These gun owners were concerned about safety and storage. And they were interested in correcting what they saw as some dangerous practices among fellow gun owners.

They also were concerned about gun deaths, all of them. And the ones often hitting close to home were gun suicides. They wanted to do something about it.

Photographer Mike De Sisti and I traveled to Park Falls to see Chuck Lovelace. We learned about efforts by Lovelace and other gun shop owners to tackle suicide by using their shops to hold guns for people in crisis.

As reporting continued, O'Brien Fellowship director Dave Umhoefer asked me: Can we do this project without any even subtle shaming of gun owners, but just tell their stories respectfully? This guided my approach to the reporting.

I had lunch not too long ago with my friend, retired Journal Sentinel columnist Jim Stingl.

I told him about the series. Stingl liked the idea of just talking to people who own guns and getting into their stories. It’s what he did for years as a columnist at the Journal Sentinel.

He also suspected it was the kind of story that other journalists were not able to see.

“I bet you won’t hear footsteps on that one,” he said.

Terms in gun coverage matter

So what have I learned in this project?

There isn’t really a “gun community.” I have found a lot of different people who own guns from different parts of the state, different political backgrounds, races, genders and ages.

I interviewed a conservative retired Navy SEAL and a socialist gun owner. They had a lot of the same things to say about safety, storage and training.

Rob Pincus, a gun safety instructor from Colorado, shared his message of what responsible gun practices look like, which includes mental wellness. Pincus was clear that there are specific audiences who need to hear the message more than others.

Pincus said he is not so worried about the guy who is working on mindfulness through yoga, who talked with his wife before buying a gun, and who took safety classes before ever going to shoot at the range.

“You don't have to convince him that proactive mental health care is a good idea. That guy is already on board,” Pincus said. “The guy that you got to be worried about is the one who thinks that gun represents the ultimate part of his individual capacity to be a man.”

I also learned language matters.

I have come to see problems with terms like “gun violence,” “responsible gun owner,” and “safe storage.”

These phrases are used often in news articles (to be clear, I too have used these phrases).

They can have value, but I found they also mean different things to different people. An editor taught me a long time ago to avoid catchphrases that may be unclear. Instead, be more specific, he said.

Consider gun violence. What does it mean? It certainly includes fatal shootings and non-fatal shootings. But what about pointing a gun at someone? Or announcing to someone who is threatening you that you are armed?

When I was 13, my dog was shot, we suspect by an angry neighbor in the rural area where my dad lived. Is that gun violence? Felt pretty violent to me.

I have come to understand how differently people see guns. Some people who don’t own guns may view them as inherently dangerous, while gun owners may see them as providing safety. So the word "safety" has different meanings.

I also noticed that guns are often compared to other things, but it seems to me they are really not like anything else. There are similarities to, say, a swimming pool (and the idea of having a dangerous thing in one's home) or a car (when noting the need to register potentially dangerous things). Guns are also their own thing. They are in the Constitution and also they are designed for one purpose.

“These were not made to shoot cans,” said Pharris, as we were shooting at a range in spring.

I also was struck by the diligence by which Pharris and other gun owners I interviewed took safety. They said they understand the risk they take by having a firearm and so a high level of care and thoughtfulness needs to go into how they train and keep their guns.

They want that same message to get out to others, including the millions of people who bought their first gun during the pandemic.

A different kind of gun researcher

In the world of experts, I also found there are differences. A number of researchers flatly state the safest house is the one without a gun. The numbers do back them, yet that message may not be the most effective, others observe.

Emmy Betz, a Denver doctor, likens that message to saying "the only safe sex is no sex.” There are millions of guns and people generally are not going to get rid of them, she said.

“Do I think we all should educate the public about the potential risks of owning a gun? Sure. But I think to say the only model we should put out there is this sort of abstinence approach, I just feel like it is missing the opportunity to help prevent injuries and deaths.”

This message of meeting people where they are has had great appeal. And I feel like that’s what I do on my best days as a reporter: Set aside what I think I know about something and just hear someone’s story.

A reporter and friend once likened our job to the questions an angel asked Hagar, pregnant with Ishmael, after she fled to the wilderness, as recounted in the Hebrew Bible:

“Where have you come from and where are you going?”

Those questions have driven me on this project.

I know a lot is written about guns, but I feel like something new may be happening. I hope this series sheds some light on that.

Author Brene Brown once wrote that storytelling is “data with a soul.” That was the idea with the series name, “Behind the Gun” – to show you, the reader, the numbers you may not know and also to share the people behind the gun.

I hope I can live up to that.

Jean Papalia, a retired Madison police officer, advised this approach: Tell their story in a way that endures. Every person has a story and their death may just help someone else live, she said.

“They don't die silently.”

Project credits

Contributing reporter: Natalie Eilbert, Alex Rivera Grant, Ben Schultz

Data analysis, graphics: Andrew Hahn, Daphne Chen, Kevin Crowe, Eva Wen

Photos, video: Mike De Sisti, Bill Schulz

Story editing: Greg Borowski

Photo editing: Sherman Williams, Berford Gammon

Copy editing: Ray Hollnagel, Pete Sullivan

Design: Kyle Slagle

Social media: Ridah Syed

About this project

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporter John Diedrich examined the full extent of gun deaths in Wisconsin during a nine-month O’Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University.

The project reveals the full picture of gun deaths in the state and tells the stories of people affected by gun deaths and those trying to find solutions.

Diedrich was assisted in the project by Marquette student researchers Alex Rivera Grant and Ben Schultz.

Marquette University and administrators of the program played no role in the reporting, editing or presentation of this project.