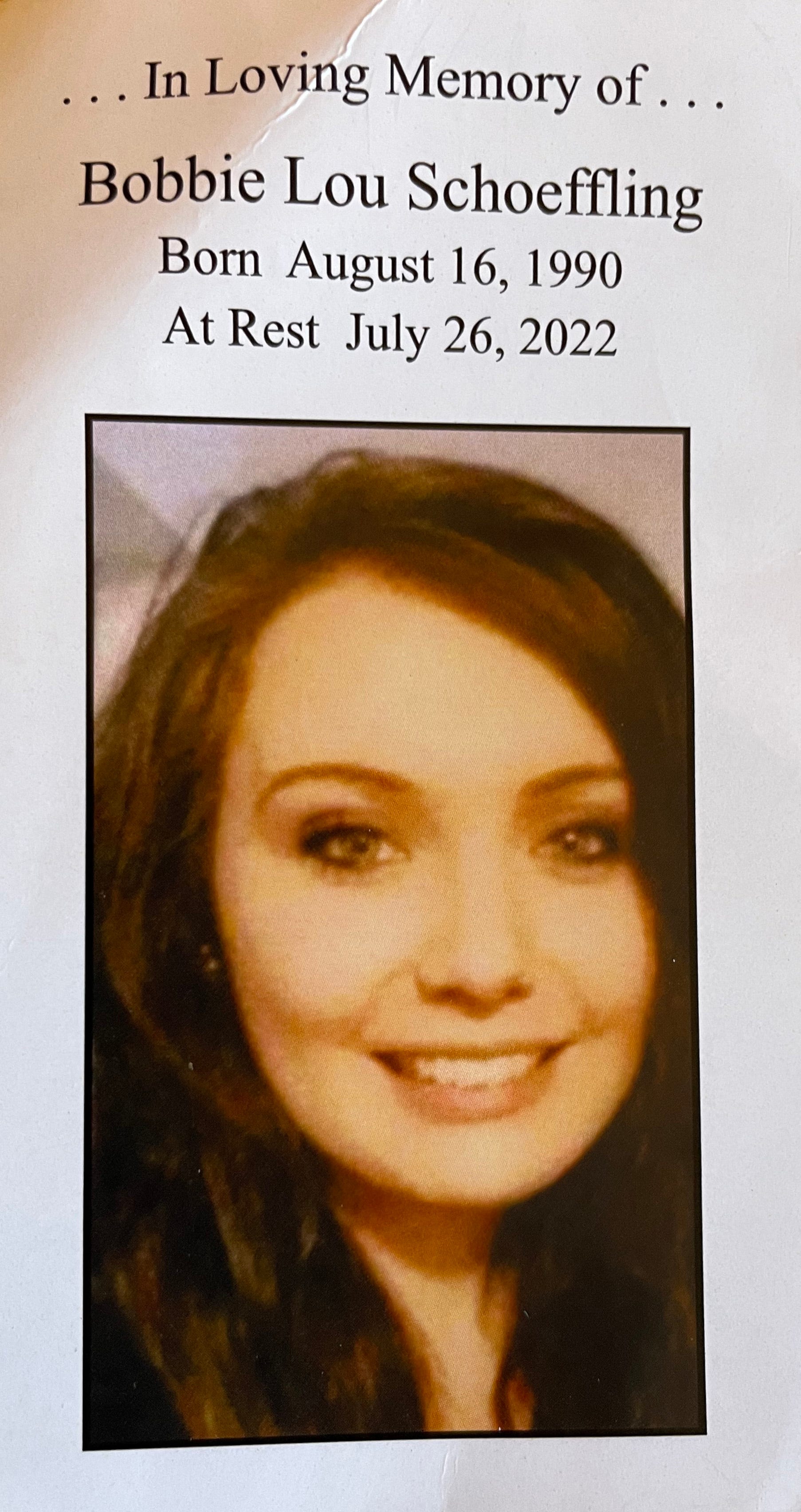

Bobbie Lou Schoeffling died in Milwaukee in July 2022 after making multiple attempts to report domestic violence to police.

Editor's note: This story describes domestic violence and includes descriptions of violent acts. Readers experiencing domestic violence can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 800-799-7233 and reach out to local resource groups for help.

Bobbie Lou Schoeffling asked for help.

Over and over again, she called 911.

She told Milwaukee police her ex-boyfriend beat her, ripped her hair out, held her hostage, threw rocks at her house and pulled a gun on her.

She pleaded with dispatchers, officers, his probation agent — anyone — to arrest him. They'd had the authority to do so for months: He had an open felony warrant for fleeing police in a high-speed chase. He could be put in jail without her cooperating or testifying or picking him out of a lineup.

She was afraid he would kill her if she talked to police and shoot any officers who tried to arrest him. She said he had made it clear he would never go back to prison.

Still, Schoeffling walked into a Milwaukee police district station last summer and told an officer her ex-boyfriend had attacked her 30 minutes earlier, while they were in her car with her two young sons.

“I’ve been here a million times, nothing ever happens,” she told the cop. “He goes on high speeds, you guys don’t catch him. He pulls guns out, you guys don’t catch him.”

“I’m really scared,” she said in an exchange captured by security cameras.

Her ex-boyfriend was finally arrested July 27 — one day after Schoeffling was found dead with multiple gunshot wounds. She was 31.

He went back to prison but not for a homicide. The state Department of Corrections, which had at least three earlier warnings about allegations against him, decided to revoke the man’s extended supervision in an unrelated gun case.

Police officers, prosecutors and probation agents who had contact with Schoeffling over the final 10 months of her life missed the full picture of an escalating series of domestic violence allegations and calls for help, a Milwaukee Journal Sentinel investigation has found.

The news organization interviewed those closest to Schoeffling, reviewed hundreds of pages of public records, uncovered video of Schoeffling reporting the abuse to police, pushed public officials for answers and asked several experts who work with domestic violence victims to review materials.

The results show how a system that is supposed to protect people like Schoeffling and the wider community failed to arrest or even question the person she repeatedly accused of violence.

The implications could not be more urgent. Forty-one lives were lost in domestic violence-related homicides in Milwaukee County last year — six of them occurring the same month Schoeffling died. Just last month, Milwaukee's police chief called domestic abuse "a root cause of a significant amount of violence in our city."

Schoeffling’s ex-boyfriend, Nicholas Howell, 29, was charged recently with first-degree reckless homicide in her death. He also faces charges of stalking and felony victim intimidation, as well as misdemeanor disorderly conduct and battery.

Howell did not enter a plea at his first court appearance. The attorney who represented him then did not return a reporter's calls. A hearing is set for next week for a judge to assign him a public defender. Prior to this case, he had not been charged in any earlier instances of domestic violence reported by Schoeffling. He did not respond to a letter from the Journal Sentinel.

Among the evidence cited in the homicide charging document is video uncovered by the Journal Sentinel. That video — showing Schoeffling walking into a police station and reporting abuse — vividly illustrates the uphill battle domestic abuse victims face when seeking help and accountability for those who hurt them, experts said.

The Milwaukee Police Department opened an internal review after the Journal Sentinel raised questions about how the officer in the video treated Schoeffling.

Antonia Drew Norton, founder of The Asha Project in Milwaukee and a national expert in domestic violence, watched the video and called it “disturbing.”

“They blamed her,” she said of the police response.

“This woman, she's terrified,” she continued. “Because if you fail to put him away, he's going to come back and she could be dead.

“Which she is.”

‘Honest, loving and caring’: Bobbie Lou Schoeffling remembered as devoted mom, sister

Tia Schoeffling set the photos down one by one.

There’s Tia and her sister, Bobbie Lou, sitting in a car wearing pink tank tops and sunglasses, both still in elementary school.

There’s Tia and Bobbie Lou on horseback a few years later.

There’s Bobbie Lou posing with a diploma and roses.

There’s Bobbie Lou with her sons — in a sunflower field, in a pool and in a selfie.

“She was the most honest, loving and caring person,” Tia said. “I looked up to her like my mom. She was my older sister, as well as my best friend.”

Bobbie Lou was five years older than Tia. The two had August birthdays, separated by three days. They celebrated together every year.

The sisters and their brother were raised by their maternal grandmother in a rural community about 30 miles outside of Milwaukee. Bobbie Lou worked as a certified nursing assistant taking care of elderly people and as a hairstylist.

She had her first child when she was 21. Her second arrived two years later. The pregnancies were unplanned, her sister said, and Bobbie Lou and her family raised the boys.

“Bobbie Lou grew tremendously after becoming a mother,” Tia said. “She is — she was the best mother. … She took that responsibility and she accepted it.”

Bobbie Lou had primary custody of her boys throughout her life. Her relationship with the father of her youngest son was abusive. He was convicted of child abuse and domestic violence during their time together, according to court records.

Bobbie Lou struggled with alcohol and was charged several times with drunken driving or driving with a revoked license. She once told an officer who arrested her that she drank as a “coping mechanism.” A therapist later wrote to a judge that her alcohol use was not the result of addiction but rather an attempt to deal with trauma.

Her legal problems meant she came under the supervision of the Department of Corrections — an agency she would later turn to for help.

Court files show a woman trying to do what the system said she should. In 2020, Bobbie Lou sent a handwritten letter to a judge in her drunk driving case, worried she was not receiving mailed notices of upcoming hearings and unsure how the new coronavirus pandemic would affect the scheduling.

“I just want to be sure I do not miss any court dates,” she wrote.

The same year, she started talking to a new guy she had met on Facebook.

His name was Nicholas Howell. Everyone called him by his nickname, Chase.

Sister sees signs of an abusive relationship

Tia was there the first time her sister met Howell after chatting with him online.

“He came off nice,” Tia said. “He came off caring.”

Bobbie Lou had gotten to know him during the pandemic. Online, Howell showed off his skills as a rapper and showered her with affection.

As the relationship went on, Tia noticed a change in her sister. Bobbie Lou was constantly on her phone, answering Howell’s calls and texts. He wanted to know where she was and who she was with.

Tia said he often accused her sister of cheating and was jealous. She remembered a time when Howell pulled up unannounced at a gas station where she was with her sister. He wanted to make sure Bobbie Lou was where she said.

“She always told me, ‘He doesn’t like when I’m with you,’” Tia said. “And I always thought that was a red flag, that that was possessive behavior.”

Bobbie Lou found an apartment in Milwaukee and Howell moved in with her. After that rental flooded, she moved to a duplex near North 91st Street and West Hampton Avenue. Tia said her sister did not want Howell to join her and even considered not telling him where she was going.

“They were having problems then,” Tia said. “But then something changed. I don't know if he sweet-talked her, but she ended up letting him stay.”

Tia also moved in, despite the uneasy relationship she had with Howell. She was in her bedroom one day when she heard shouting and then a large bang, like someone had been shoved into a wall.

She ran to the living room and found “everyone kind of scrambled.”

Tia pleaded with her sister to end things with Howell and Bobbie Lou tried to do so — at least eight times that Tia remembered.

Howell would leave the house, only to return a few days or weeks later.

“She kept going back to him,” Tia said. “I didn’t understand why. I thought maybe she knows something about him. Is there something that I don’t know about them? That they have a special bond?”

She paused.

“Sometimes you fall in love with the wrong person,” she said softly.

People stay in abusive relationships for many complicated reasons. They might financially depend on their abuser or share children. Experts say one of the key reasons is safety. It might sound counterintuitive to people who have not experienced abuse. To them, leaving seems safer. For those living with abuse, it often is not.

Domestic violence is about power and control. When a person leaves, an abuser loses both of those things and might take dangerous steps to regain them.

“People choose to stay because the alternative could mean homicide,” said Jenna Gormal, co-director of prevention and engagement for End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin. “It can be a very tactical decision.”

The isolation Bobbie Lou experienced is common in domestic violence and makes it much harder to leave. Advocates often cite the statistic that on average, it takes seven attempts for someone to leave an abusive relationship permanently.

Complicating the situation was Howell’s probation status.

He had two prior convictions. The first was for an armed robbery on Milwaukee’s west side. The second was for illegal gun possession. He was sentenced to three years in prison in that case and was released on extended supervision in late 2019.

If Bobbie Lou called police, Howell could be forced to serve out the rest of his time behind bars. And he had made it clear to her that he had no intention of going back to prison.

He soon came to the attention of police anyway.

Shortly before 1 a.m. on March 10, 2021, Germantown police pulled him over for driving with a suspended license. He stopped at a gas station and got out of his car. The officer asked a colleague to come with a police dog. The dog started barking, a signal that it may have detected drugs, and Howell sprinted back to his car and took off.

Germantown police chased after Howell, reaching speeds of more than 100 mph before losing sight of the car in Milwaukee.

The Germantown officer notified the Department of Corrections about the chase, and officials issued a warrant for a probation/parole violation.

Washington County prosecutors later charged Howell with fleeing and obstructing an officer.

Police officers and probation agents could have arrested him at any point.

Instead, he remained free for more than a year.

Domestic violence escalates with assaults using a gun

Tia has a clear memory of a night in October 2021.

She was at Bobbie Lou’s house on Hampton Avenue in Milwaukee.

Howell was there. He didn’t want Bobbie Lou to leave. He and Bobbie Lou argued, and he punched her. His shirt inched up and Tia saw a flash of metal.

Crack.

The butt of a 9mm came down on Tia’s head. Then, Howell turned the barrel to her temple.

“Shoot me, then,” she remembered saying.

She ran to her sister.

For some reason, he didn’t shoot.

Bobbie Lou grabbed for the gun, tussling with Howell, until she broke free and ran to her car with Tia.

Bobbie Lou and Howell had been dating for about a year. His jealousy and possessiveness — the calls and texts at all hours — had been relentless. Her injuries — bruises and cuts along her hands and face — became impossible to hide.

That night, Bobbie Lou decided to call police.

She told three Milwaukee officers that Howell had punched her in the head and then hit her sister with a pistol when she tried to defend her.

Bobbie Lou repeated what Howell had screamed at her.

Bitch, I’ll kill you.

She’d had problems with him in the past, she said, but hadn’t called police, fearing he’d get in trouble.

The officers took photos of Bobbie Lou’s bruises and cut, and the knot on Tia’s head. Both said they did not need medical treatment for their injuries.

The officers put a temporary alert out for Howell as a suspect in a battery and felony gun investigation. Two officers checked two addresses for Howell but did not find him.

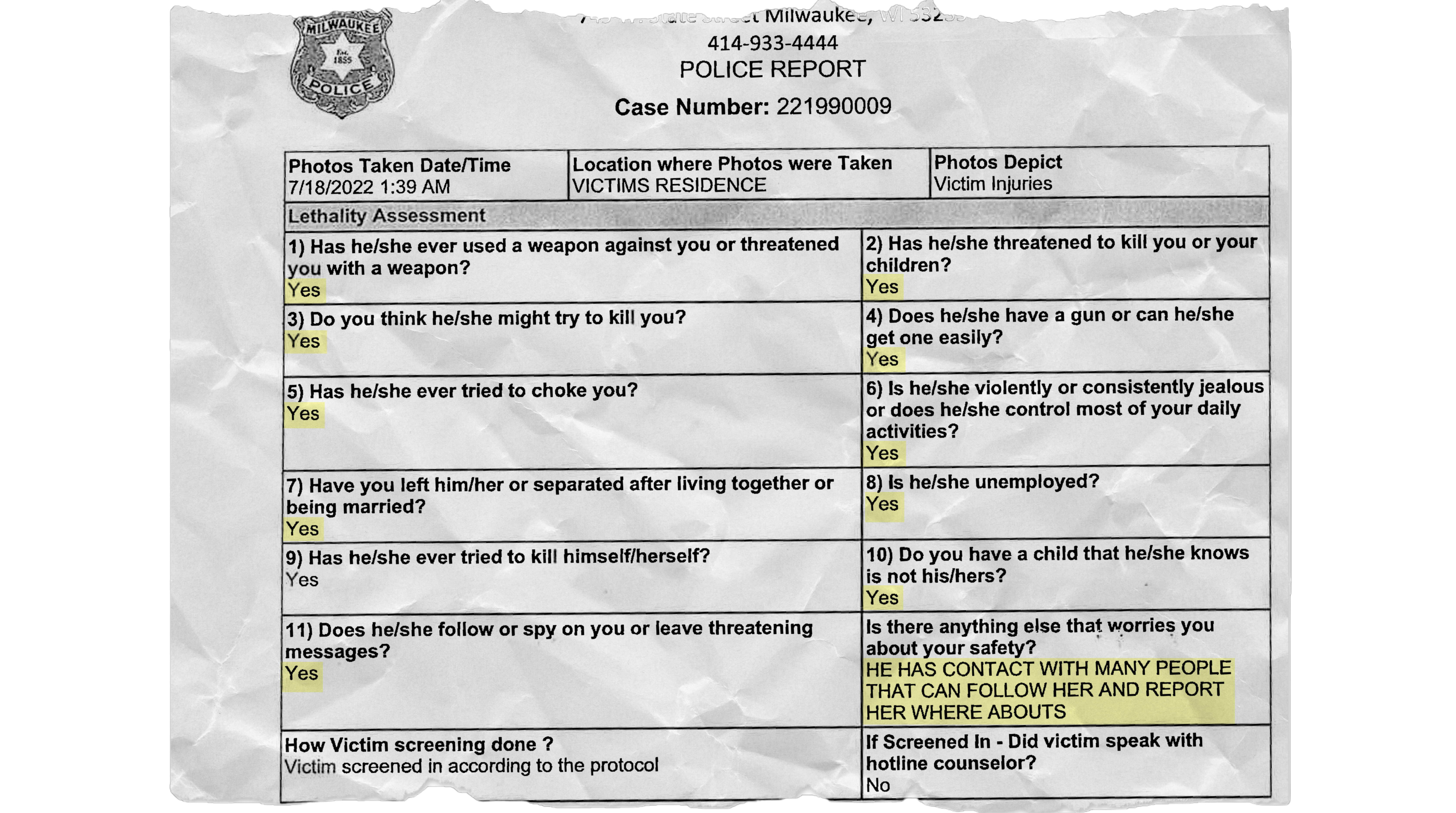

Bobbie Lou said her ex-boyfriend had a gun and threatened to kill her. That meant she would have screened in as higher risk on a lethality assessment, a form police officers use to identify domestic violence cases likely to end in death.

The 11-question assessment asks about threats to kill a victim or her children, attempts to strangle her, jealousy and control, employment status, access to a gun and other red flags.

The form helps officers and others convey to victims like Bobbie Lou the level of danger they’re facing. It also is used to connect victims with domestic violence advocates, who find victims shelter and file restraining orders. The assessments also are reviewed weekly by a team of specialists dedicated to stopping domestic violence homicides.

All police agencies in Milwaukee County have been trained on the form since 2014. The Milwaukee Police Department requires officers to fill it out when responding to a domestic violence call.

But the officers did not use a lethality assessment on Bobbie Lou. And they did not classify this as a domestic violence call at all.

No arrest and no charges in first case

Ten days passed.

A prosecutor called Bobbie Lou to talk about the reports police had sent. For a case to be charged, she would need to cooperate, he said.

Bobbie Lou was scared and frustrated. Howell had not been arrested — and she did not understand why.

She had told police about the beating. Her sister had described it to the Department of Corrections, the agency in charge of monitoring Howell. The department’s agents had the power to detain him at any time for suspected violations of his extended supervision.

Yet, he was still free.

Why do you think that a woman is going to call the police the next time something happens after they failed her the first time?

On the phone with the prosecutor, Bobbie Lou said she was afraid of what Howell would do if criminal charges were filed when he was not in custody. She had told her sister several times before that Howell said he would rather have a shootout with police than go back to jail.

The prosecutor, William Ackell, asked to call her back along with a victim advocate. The next day, in a second call, she reiterated her fears and made her decision.

She would not cooperate anymore in the case.

“She was very clear that she did not intend to participate in a prosecution on that matter,” Chief Deputy District Attorney Kent Lovern said.

His office did not file charges.

Looking back, Tia pointed to this moment as a significant one.

“Why do you think that a woman is going to call the police the next time something happens after they failed her the first time?” she said.

The district attorney’s office was “concerned” about the serious allegations involving a gun, which is why they wanted an advocate to speak with Bobbie Lou, according to Lovern.

Despite that, no one from the office took any additional steps to figure out what was going on. The advocate could have done a lethality screening but did not.

The prosecutor, or police department, could have sent the reports to the county’s Domestic Violence High-Risk Team, but did not. The team includes officers, detectives, prosecutors, victim advocates, probation agents and social service providers who discuss how best to intervene to keep victims safe and hold offenders accountable. In five years, the team has handled more than 3,100 cases, with only one ending in a homicide.

Howell’s probation agent, Gerhard Vosswinkel, received a report about the October assault, according to a log he kept. There are no entries after that point describing attempts to contact or find Howell.

It was not the first time Vosswinkel had received a report alleging Howell had abused someone.

Less than two years earlier, before Howell started seeing Bobbie Lou, a different woman called Vosswinkel and said Howell had beaten her daughter. The woman said her daughter was bruised but did not want to go to police and get Howell in trouble.

Vosswinkel questioned Howell, who denied the allegations. The same day, Howell’s girlfriend contacted the agent and denied Howell had hurt her.

A high-speed chase in Butler when her life was 'in jeopardy'

Bobbie Lou became pregnant with Howell’s child sometime in the fall of 2021. She stopped drinking.

She worried about Howell’s response to her pregnancy, and with good reason: Homicide is a leading cause of death in pregnant women in the U.S.

Three weeks after Bobbie Lou visited doctors for an ultrasound, she told her sister that she’d been involved in a high-speed chase with police — driving while Howell, in the passenger seat, held a gun to her.

According to a report from Butler police, on the night of Jan. 2, 2022, Officer Kyle Knapp noticed a black Mazda with a broken brake light and missing front license plate in the parking lot of a Kwik Trip.

He saw a woman slip into the driver’s seat as a man with long dreadlocks got into the passenger’s seat. The car quickly reversed and left the parking lot.

Knapp tried to pull it over.

At first, the car turned into the parking lot of the nearby Home Depot on North 124th Street as if it was going to stop. But then the driver made a U-turn and sped away.

Knapp chased after it, sirens screaming. The three-mile pursuit lasted only two minutes until Knapp decided it was too dangerous and stopped.

But he wasn’t done investigating. He pulled security footage from the Kwik Trip, which showed two children had been with the pair inside the store. He sent an alert to other police agencies with photos of the woman and man.

An officer in New Berlin ran the images through facial recognition software, which identified the woman as Bobbie Lou Schoeffling and the man as Nicholas Howell. Howell's result had a 100% accuracy reading.

Knapp went to Bobbie Lou’s listed address on Hampton Avenue and, spotting the Mazda parked nearby, knocked on the front door. No one opened it. He towed the car.

Two months later, Knapp tracked down Bobbie Lou.

She was in the Waukesha County Jail where she had just started a 90-day sentence with work release on a drunk-driving conviction. The case was from a traffic stop the summer before.

She had been sober and pregnant for much of the time since then. She told Knapp she’d had a miscarriage a week before she went to jail.

When Knapp questioned her, Bobbie Lou admitted the person in the Kwik Trip photo looked like her but initially denied leading him on a high-speed chase.

Knapp tried to build rapport, saying he thought she had been in a “bad situation.”

“My life was in jeopardy,” she said. “I had a gun to me ... I wanted to pull over. I don’t know if you could tell that. I slowed down, I wanted to.”

“I did see you slow down,” he said.

“I had a gun to me and it was either a police officer or I was going to get shot,” she continued. “That’s what was being screamed at my face and I did not want that to happen, whether it be me, you or someone else get shot.”

She told the officer that her passenger stuck a gun under her ribs when she tried to stop at the Home Depot and kept it there for the rest of the chase.

Knapp asked if the passenger was Howell and showed her the Kwik Trip security photos.

No, Bobbie Lou said. She gave a different name.

He asked about the two children in the car. She said they were the man’s nephews.

Knapp confirmed with her where the passenger pulled the gun: Home Depot, on the Wauwatosa side of North 124th Street.

"So that’s when the gun incident happened and that never then went back into Waukesha County," he said, before asking her: “For jurisdiction reasons, if we find this guy, like, would you be willing to file a complaint against him?”

“I mean yeah, if I can identify him," Bobbie Lou replied.

What she had described the man doing was much more serious than fleeing a traffic stop, Knapp said. He said he would talk to the prosecutor and explain the situation. She didn’t believe him.

“I just don’t trust the system anymore,” she said.

Knapp sent the case to the Waukesha County district attorney’s office for potential charges against Bobbie Lou. He included her account of being held at gunpoint.

Knapp had pulled Howell’s criminal background after receiving the facial recognition lead. He saw two open warrants, one from Washington County for fleeing and one from the state Department of Corrections for a probation violation.

His reports make no mention of any attempts to find or interview Howell.

Knapp searched several databases for the name Bobbie Lou had given him. He did not find anyone with that name who matched the Kwik Trip photos.

Although Knapp had implied to Bobbie Lou that Tosa police needed to investigate the gun offense, that was not accurate, Butler Police Chief David Wentlandt told the Journal Sentinel.

“We have jurisdiction on both sides of the street," he said.

The chief had no record of his department notifying Tosa police of Bobbie Lou's account: that a man had put a gun against a pregnant woman’s ribs, threatened to shoot her and forced her to flee from police at dangerous speeds with two children in the backseat.

The officer tried to determine who the passenger was but was given inaccurate information, Wentlandt said.

"He ran into a dead end," the chief said.

A bruised lip, a 911 call and a woman 'fed up with him not getting caught'

After she finished her work-release jail sentence, Bobbie Lou continued to live in fear of Howell. She had tried to end things, but he would not let go of the relationship.

She had told police and others that he had threatened her. Stalked her. Beaten her. Held her at gunpoint.

Every time she tried to get help, nothing changed.

Meanwhile, Waukesha prosecutors had charged her with fleeing in the Butler case.

One night in June 2022, Tia went over to her sister’s house to hang out. The two sisters walked into the hallway where, under the light, Tia noticed her sister had a swollen, bruised lip.

She believed Howell had hurt Bobbie Lou. The second Tia saw Howell inside, she started punching him.

“He once again took his gun out and pointed it at me,” Tia said. “And my sister once again jumped in between us.”

Tia ran out to her car and called 911. She said Howell had threatened her with a gun and her sister was in danger.

Before the line went dead, she shared two more pieces of information. Howell was wanted by police and she feared he would kill her for calling 911.

Police called her back 15 minutes later.

“Doesn’t matter, he is gone now,” she said. She declined to share her name or location, saying she no longer needed police.

An officer called her at 11:32 p.m. and left a voicemail.

At 11:39 p.m. — nearly 50 minutes after Tia first called 911 — the dispatch records noted that officers checked the residence and “heard no movement or distress. The unit appears to be vacant.”

Tia told the Journal Sentinel her sister was “fed up with him not getting caught.”

“She had just given up at that point,” Tia said.

Police video shows Bobbie Lou saying, 'I'm gonna die. He's gonna kill me.'

A month later, on July 11, Milwaukee police dispatchers got another call from the Hampton Avenue address.

This time, a caller said a friend’s boyfriend was hitting her. The line was disconnected. Both times police called back, it went to voicemail.

Officers Shaundae McIntosh and Michael Budziszewski headed to the address and found Bobbie Lou and a friend. The two women were outside in the dark. The officers asked what happened and if Bobbie Lou could identify her ex-boyfriend.

“I can’t tell you guys because he really will come kill me. I’ve tried this before, I’ve tried this before and I’m sorry but like I can’t ever," Bobbie Lou told them in a conversation recorded by McIntosh's body camera.

"He always pulls up and just smashes in my windows and just does stuff and I just can't, just can't get rid of him. ... He (is) saying he is gonna have a gun, pull up here and shoot up my house," she said.

The body camera also captured footage of Bobbie Lou's friend hugging her and telling her they were going to fix the situation. Bobbie Lou responded: "No, we're not. I'm gonna die. He's gonna kill me."

The officers did not file an incident report. That left no detailed written record of what happened and no case to refer to prosecutors. Dispatch records showed the officers closed the call as "advised," which meant they believed there was not enough information to determine a crime was committed.

The friend who was with Bobbie Lou that night told the Journal Sentinel she pointed at Howell's fleeing car as officers arrived, telling them: "That's him, right there."

Bobbie Lou also told the officers her ex-boyfriend had held her at gunpoint during a high-speed chase and had shot into her home, according to her friend, who asked that the Journal Sentinel not publish her name for safety reasons.

“She told him there was a bullet hole in the house that night,” the friend said.

Asked if Bobbie Lou did not want officers to file a report, her friend replied quickly.

"No, we wanted him caught," she said.

Instead, the officers said to call back if anything else happened, she said.

Bobbie Lou did call 911 again that night.

At 10:45 p.m., she asked officers to come back because Howell was threatening to burn her house down, beat her and damage her car. She said she was leaving her house to stay with a friend.

More than an hour later, two different officers were sent to the Hampton Avenue address. Those officers cleared the call with another "advised" label.

There is no record of officers searching other addresses for Howell that night, even though he already was wanted on two warrants unrelated to domestic violence.

To Bobbie Lou, no one seemed able or willing to catch him.

'They blamed her': How Bobbie Lou was treated by Milwaukee police when she reported further abuse

On July 15, Bobbie Lou's friend again called Milwaukee police, frantic.

A man was beating Bobbie Lou inside a car, in front of children, she said.

Within an hour, Bobbie Lou and her friend walked into Milwaukee Police District 3, a station near the intersection of West Lisbon Avenue and North Avenue. Bobbie Lou’s two sons, ages 10 and 7, were there, too.

What happened next deeply disturbed those who help domestic violence victims.

Bobbie Lou told the officer her ex-boyfriend was driving recklessly in her car, so she reached over and threw it into park. The car jolted to a stop near a sidewalk. Then he started beating her, she said.

“I’ve just been trying to break up with him,” she told the officer. “He shows up at my house all the time. We just called the police on him again the other day.”

She provided Howell’s name, birth date and physical description, adding: “He’s very highly, highly dangerous just so you guys know.”

She answered the officer’s questions: No, they do not have children together. Yes, they used to live together on and off.

“He like won’t leave and he holds me hostage. Like literally, I can’t leave my house for days,” she said. “He takes all my shit, he takes my phone, I can't do shit.”

“I’m just tired, I shouldn’t have to live like this,” she added.

The officer, Shawn Toms, looked up Howell’s record. He did not see a report from four days earlier when Bobbie Lou and her friend called 911, because none of the officers filed one.

Toms did see the October 2021 incident when Howell was accused of beating Bobbie Lou and her sister. He noticed no charges had been filed.

Howell had not been arrested in that case. Nor had he been arrested at any point in the year his warrant in the Washington County fleeing case had been open — though Milwaukee police had received three calls about him over that time period.

But Toms began to question Bobbie Lou as though Howell had been arrested, and that she was the reason he was free — appearing to blame her, as one domestic violence expert put it later, for “failing to be able to hold him accountable for crimes.”

“So what do you think is going to happen this time?” Toms asked Bobbie Lou.

“I don’t know, that’s what I’m saying, it’s like you guys can never catch him that’s why ...,” she said, before the officer interrupted her.

“Well, if we catch him and then he goes down and you don’t show up, he gets released, so that’s why I’m saying what kind of outcome do you expect today?” Toms said. “You want me to catch him again, you don’t show up, he gets released? You just keep doing this cycle, you know what I mean?”

Bobbie Lou’s friend leaned toward the desk and asked the officer: “Are you saying you don’t care?”

“No that’s not what I’m saying,” Toms said, later adding: “I’m asking what’s going to be the difference, or how does this change today, OK? That’s something you gotta think about.”

"We can write this all day long," he continued. "You can come back 97 more times but — if — I don’t know what to tell you. We’ll be more than happy to write it up, we’d be more than happy to send it down, we’d be more than happy to arrest him once again."

“Like I said, he’s been wanted for more than a year and you guys haven’t caught him,” Bobbie Lou said.

Domestic violence experts who watched the video criticized the officer’s actions.

“His vibration is like: We don't care," said Shawn Muhammad, who served as associate director of The Asha Project until his recent retirement.

It was the police’s job to hold Howell accountable, said Drew Norton, the founder of The Asha Project.

“But they blamed her,” she said.

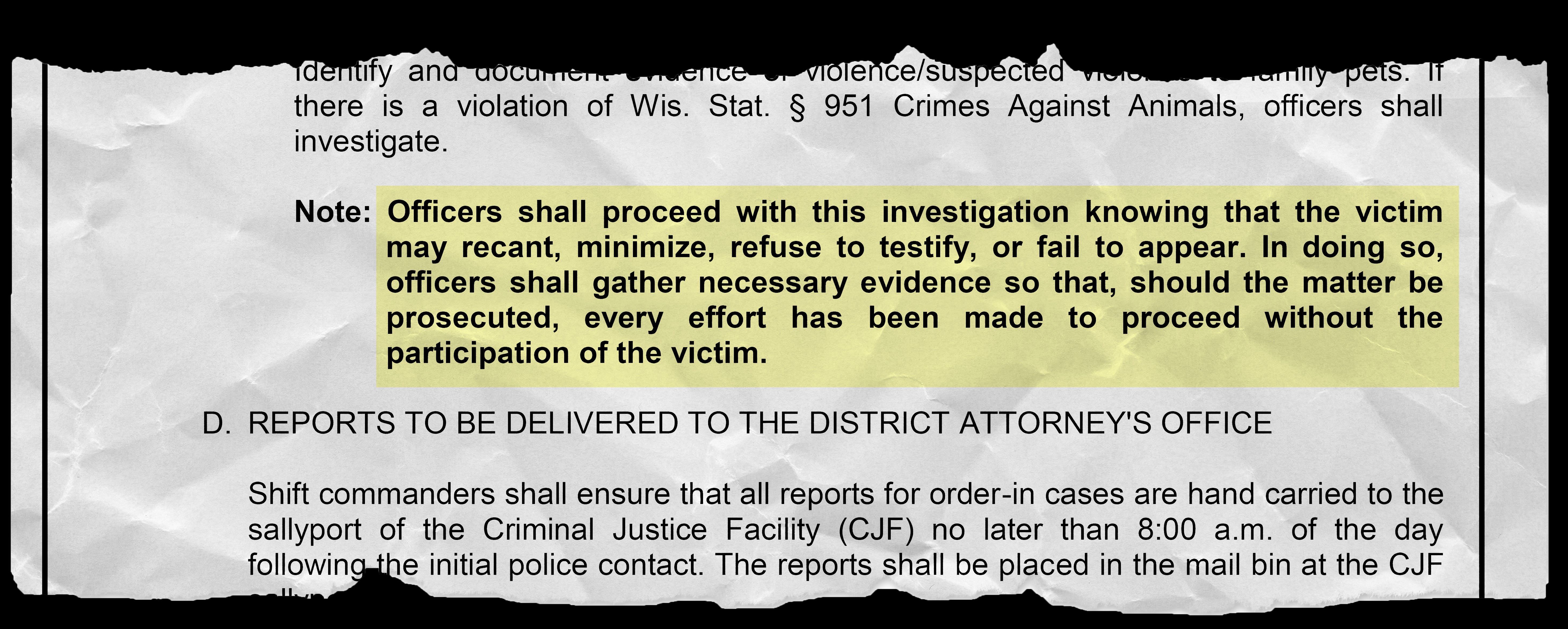

The Milwaukee Police Department has a 19-page policy on how officers are supposed to investigate domestic violence. It includes an acknowledgment that victims might recant, minimize an abuser’s action, not appear in court or refuse to testify.

The policy stresses that officers “shall gather necessary evidence so that, should the matter be prosecuted, every effort has been made to proceed without the participation of the victim.”

"We want effective, compassionate responses," said Carmen Pitre, president and chief executive of Sojourner Family Peace Center, which coordinates the county's Domestic Violence High Risk Team.

When systems work, they work well, but when they break down, they need to be held accountable, she said.

“If we don’t try to do better, we’re never going to be able to fix what’s broken or breaking,” Pitre said.

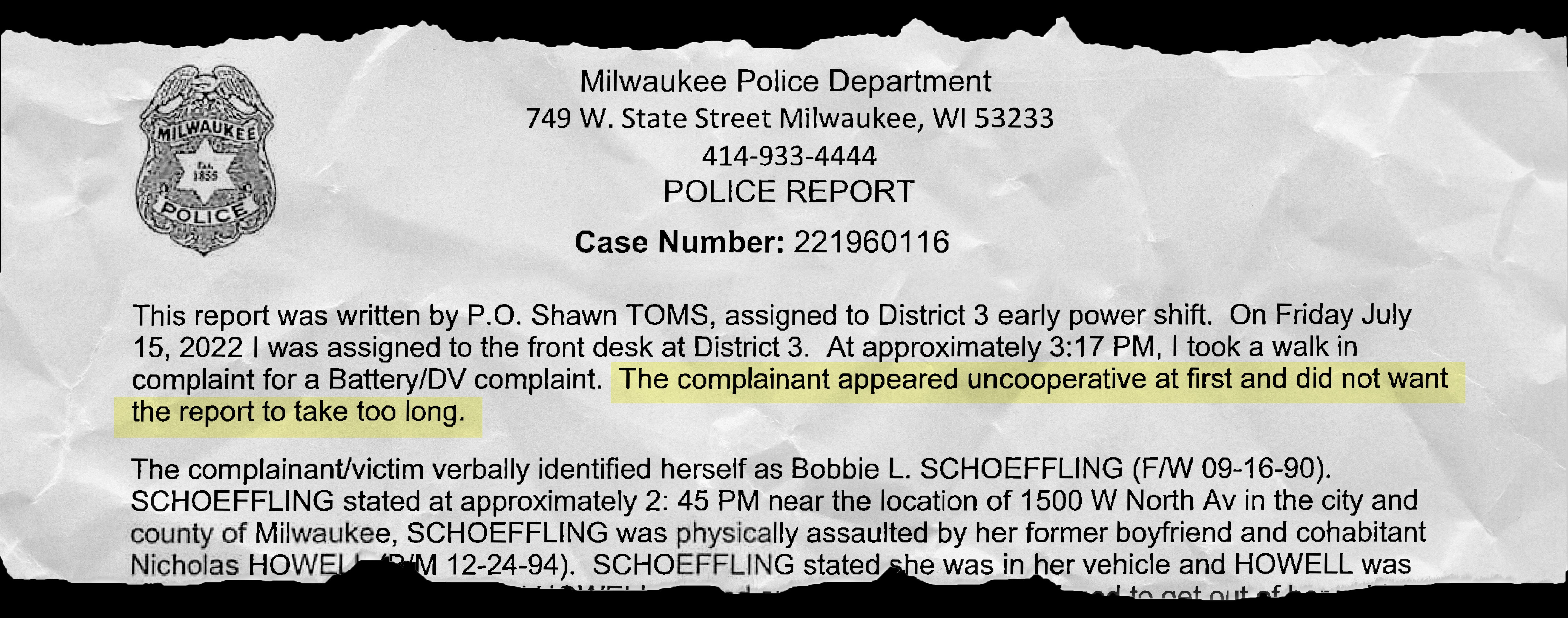

Officer described her as 'uncooperative'; his actions put under review

The officer did file an incident report based on what Bobbie Lou told him.

In the first paragraph, Toms wrote: “The complainant appeared uncooperative at first and did not want the report to take too long.”

He noted she refused to speak to a hotline counselor and did not consent to releasing her information to local domestic violence advocates who could follow up with services. The security video showed Bobbie telling the officer she already had been in touch with an advocate. Police took 10 photos of her injuries.

This time, police did conduct a lethality assessment on Bobbie Lou.

She answered yes to 10 of the 11 questions.

After she left the district, Toms can be seen on security video turning to other officers at the front desk to vent about the interaction.

“It’s our fault because we never do shit about it,” Toms said sarcastically, adding: “It’s all your fault John, everything that bitch went to go through is your fault.”

The officers briefly considered calling Bobbie Lou's probation agent to say she was spending time with a felon and was around guns. Although the officers seemed to be joking, if they had called, it could have had serious consequences for Bobbie Lou, including possible jail time or losing custody of her children.

Near the end of the video, Toms described the woman who came to him for help this way:

“She was a c--t.”

The Journal Sentinel requested an interview in December with Police Chief Jeffrey Norman to discuss the officer’s actions. In response, the department opened an internal review into the incident and declined to make Norman or another police official available to answer questions, citing that ongoing review.

The department released a statement at that time, which said, in part, it “takes community member reports of any and all violence very serious (sic). MPD holds our members to the highest level of integrity.”

It’s our fault because we never do shit about it. It’s all your fault John, everything that bitch went to go through is your fault.

The review stayed at the district level and did not go to internal affairs. Two sergeants spoke to Toms and reminded him of the department's code of conduct, which calls for officers to treat members of the public and colleagues with dignity, respect, courtesy and professionalism, according to a memo placed in his personnel file.

Toms' conversation with Schoeffling "could be construed as disrespectful," Sgt. Gregory Byers wrote.

Toms said he understood and would not let it happen again, the memo says.

The department declined to make Norman, Toms or any other police representative available for an interview about Schoeffling's prior domestic violence reports. Toms did not respond to requests for an interview.

Prosecutors again decline to file charges in domestic violence case

Three days after Bobbie Lou walked into District 3, the District Attorney’s Office decided not to file charges against Howell.

Lovern, the chief deputy district attorney, said a prosecutor and victim advocate had tried to reach Bobbie Lou without success.

“We certainly had the strong impression that there was again not a desire to be cooperative with the prosecution of this matter and no charges were ultimately filed,” Lovern said.

Because Howell was not arrested at the scene and all information came from Bobbie Lou’s account, her cooperation was necessary for a criminal case, he said.

Her case also did not get referred to the county’s Domestic Violence High Risk Team. Officials have said the team, while successful and adding staff, cannot handle all of the serious domestic violence cases happening in the county.

On the same day the district attorney’s office decided not to charge Howell, Bobbie Lou again called Milwaukee police.

Earlier that day, around midnight, she had heard Howell throwing rocks at her window. She believed he had a gun with him.

She yelled at her sons to get on the ground and called 911.

She told the operator what was happening, that Howell had beaten her a few days earlier and that she had seen him with a gun.

Howell was gone when officers arrived. Bobbie Lou said everything began with an altercation a couple hours earlier near a gas station on North Martin Luther King Jr. Drive.

Howell had driven up as she left the gas station, honking his horn and swerving before pulling in front of her and slamming on the brakes. Then he swung open her driver’s door, slapped her and violently pulled her hair before grabbing her purse and phone.

As she followed him to get her belongings, he pulled a gun from his waistband, pointed it at her chest and said, Bitch, stop playing with me.

Howell spotted a Milwaukee police wagon and squad driving by and told her to shut up. While he was distracted by the police, she snatched her phone and purse back, jumped in her car and drove home. Howell then called her phone “nonstop” and showed up at her house throwing rocks, which is when she called 911.

The officers again gave Bobbie Lou the lethality assessment. She answered yes to all 11 questions. Under victim demeanor, police described her as “fearful.” An officer asked if anything else worried her and wrote down her answer: "He has contact with many people that can follow her and report her whereabouts."

She was screened in as high risk, but declined to speak with an advocate on the domestic violence hotline.

The police noted in their report that Howell was a convicted felon who cannot have a gun and had an active warrant from the Department of Corrections and another warrant from Washington County. He still was wanted for questioning in the earlier domestic violence allegation that Bobbie Lou had made at District 3.

Officers asked Bobbie Lou where Howell might be. She gave an address. Officers checked it twice that night.

They didn’t find him.

A last call for help: ‘You need to catch him before he kills me’

One of the last times Tia saw her sister alive, she was on the phone.

Bobbie Lou was talking to Howell’s probation agent, Vosswinkel, the person who was supposed to be supervising him after he got out of prison on his gun case.

She overheard her sister tell him: You need to catch him before he kills me.

The Department of Corrections denied interview requests with Vosswinkel, or anyone else at the agency to answer questions about Howell’s supervision. Vosswinkel did not respond to interview requests. The department declined to confirm an exchange took place, citing victim privacy.

Vosswinkel knew about the Germantown fleeing case as early as March 2021, according to his case notes obtained by the Journal Sentinel in a public records request.

The notes show he also knew about the October 2021 assault.

And someone called him in mid-July 2022 to report Howell had guns and provided other information that was blacked out by the Department of Corrections, again citing victim privacy.

After that, Vosswinkel updated the existing violation warrant from the fleeing case to say Howell was potentially armed, an agency spokesman told the Journal Sentinel.

A few days later in July, Vosswinkel received a written statement about “recent incidents with offender.” The Department of Corrections denied a records request for that statement so it’s not known publicly who sent the statement or what it described. The department said releasing it could interfere with a homicide investigation.

The Journal Sentinel asked the Department of Corrections to detail what efforts, if any, the agent or other staff made to locate and question Howell in the year he was wanted. The news organization asked the agency to provide specific dates and steps taken.

Instead, John Beard, a department spokesman, released a general statement that when the agency "learns of behavior that is potentially illegal or could be in violation of an individual’s rules of supervision, the agency shares information with authorities. Once apprehended, DOC performs its own investigation that can lead to a number of responses, including recommending revocation of the client’s supervision."

Department of Corrections agents and police could have taken Howell into custody at any point from at least March 2021 onward. They did not.

Only a "very small number" of agents are dedicated to actively going out with police to find those who are wanted, focusing on those highest-risk people wanted for violent crimes, Beard said.

Milwaukee police did refer the rock-throwing and beating to the District Attorney’s Office. The Domestic Violence Unit received that case and 146 others for potential charges that week. At the time, the unit had 10 prosecutors, including the team supervisor, to review charging referrals and staff three domestic violence courts.

The case was still awaiting a charging decision when Bobbie Lou was found shot to death.

A mother trying to protect her sons leaves a legacy

Bobbie Lou sent her sons to stay with her grandmother the last weekend in July.

Her sister believes she knew the danger she faced.

Bobbie Lou started a new job at an office on July 25, a Monday. She was making plans to move and had an appointment to view a house she wanted to buy on Tuesday evening.

She never made it.

On July 26, the same friend who'd gone with Bobbie Lou to District 3 called 911 and asked police to check on Bobbie Lou after she could not reach her. The friend also called Tia, who immediately left work and drove to her sister’s house.

Tia was driving when the friend called back to tell her Bobbie Lou was dead. Tia called Howell’s probation agent and screamed at him.

She has two babies. This isn’t right. She begged you to catch him!

In the days after her sister’s death, Tia scrolled through her phone and read messages from her sister. Amid the love and jokes between sisters, she saw a record of Bobbie Lou’s relationship.

The day in March when Howell got a car and Bobbie Lou hoped it meant he would leave their duplex more often. Another day in May when he moved out. A message in July when Bobbie Lou said she had made him leave again — this time, she hoped, for good.

Bobbie Lou’s grandmother requested the pastor presiding over her funeral wear cowboy boots, a nod to the family’s rural roots and Bobbie Lou’s love of horses. When she learned he didn’t have any, she lent him a pair.

“I think you have to be a brave person to get on a horse,” the pastor said in his eulogy.

Bobbie Lou was cremated. After the service, her two brothers carried her remains to a brown horse standing outside the church.

The mourners, including her sons, watched as they placed her ashes on the saddle, tightening the hold before the horse pushed forward.

Contact Ashley Luthern at ashley.luthern@jrn.com. Follow her on Twitter at @aluthern.