Angela Peterson / Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Meet the new breed of landlord invading Milwaukee:

A couple of former Silicon Valley executives who were crewmates on the Harvard rowing team; a fast-growing Ohio company that owns more than 13,000 rental homes in 14 states; a native of Peru who has run real estate companies in Houston and Palm Beach, Fla.; and a southern California woman who was looking for a place to park her cash windfall.

This diverse group illustrates a phenomenon that could have major ramifications on the housing market in Milwaukee and other urban centers. Out-of-state companies and investors attracted by cheap properties and healthy profits are gobbling up scores of single-family homes and duplexes, as well as some apartment buildings, in Milwaukee. They rent them out, sometimes with little interest in — or knowledge of — the neighbors around them.

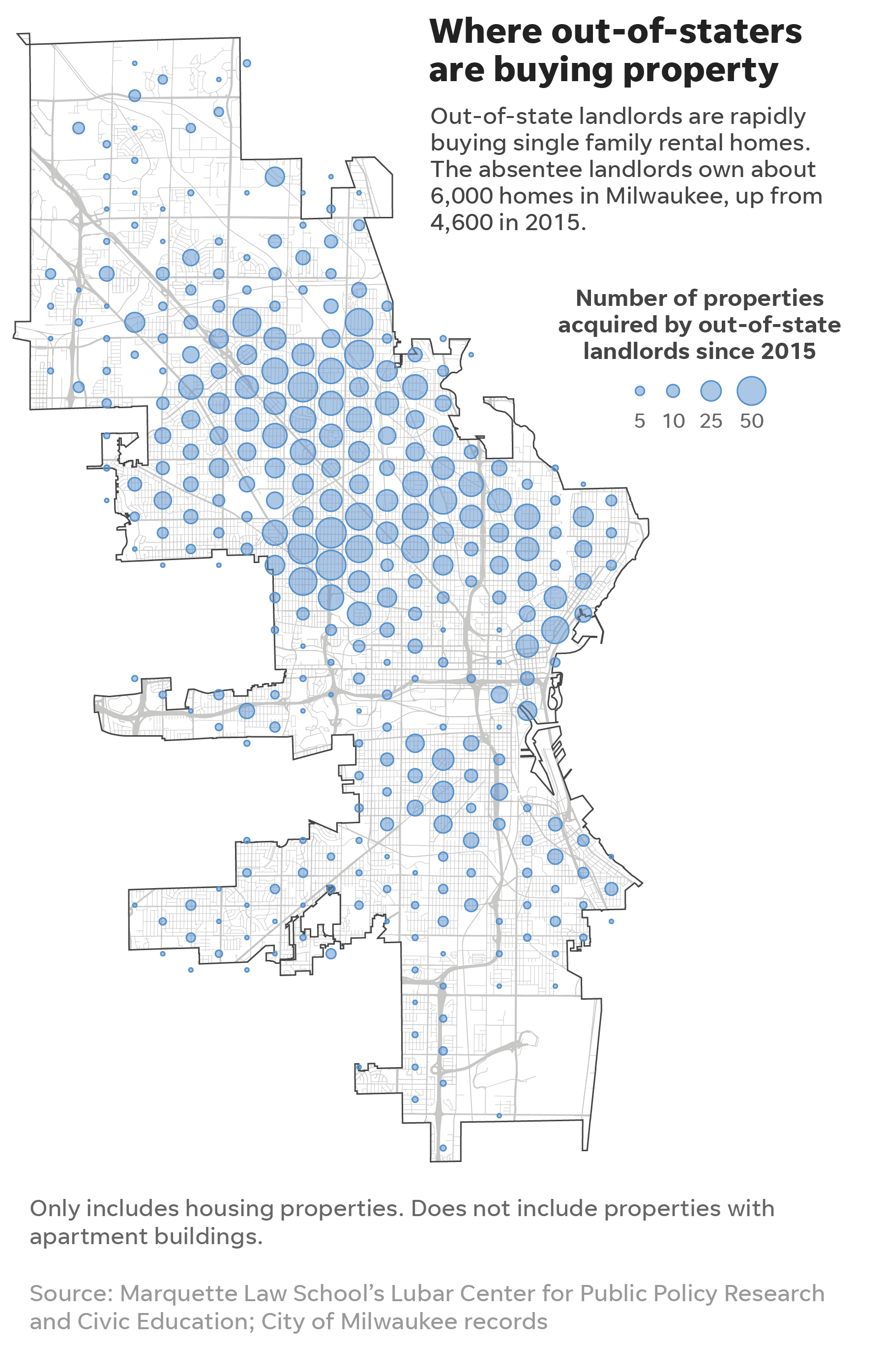

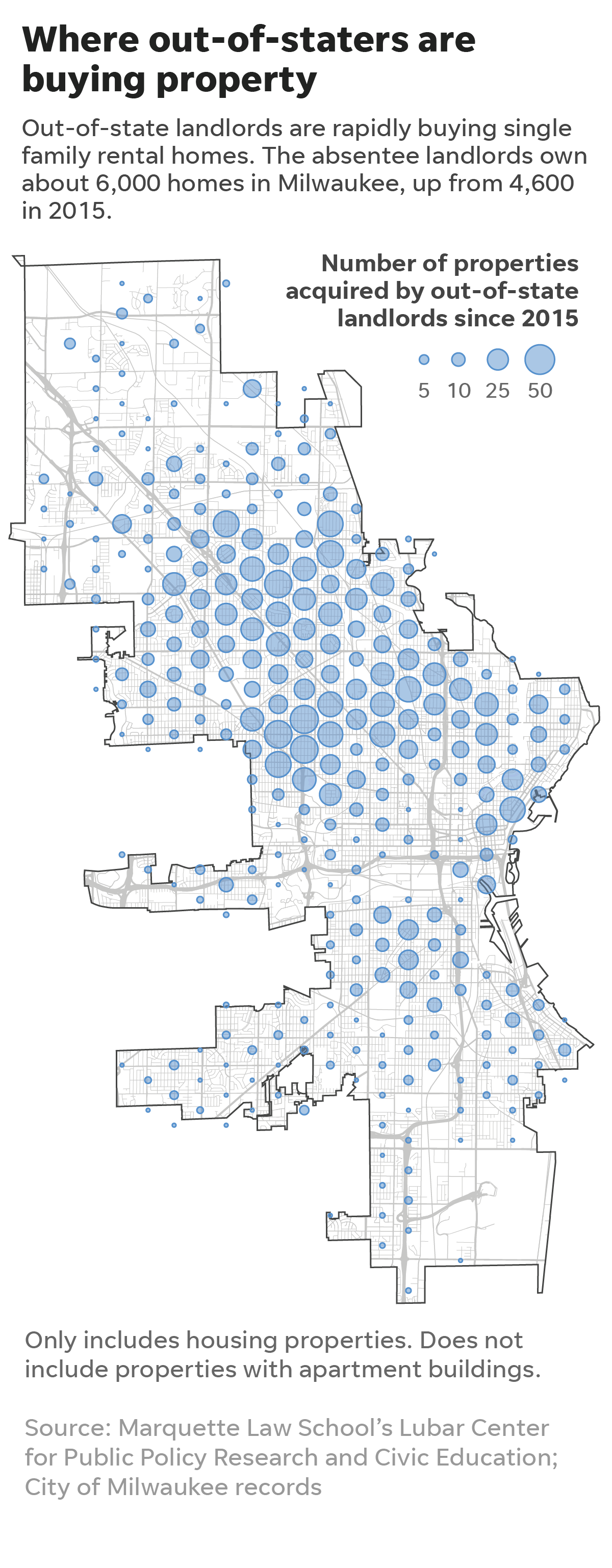

About 6,000 properties, or 14% of all Milwaukee rental homes, are now owned by out-of-state landlords, according to an analysis by Marquette Law School’s Lubar Center for Public Policy Research and Civic Education. There were 4,600 rental homes owned by out-of-state landlords in 2015, and just 1,500 in 2000.

Nationally these companies and investors buy properties in neighborhoods of all income levels. But in Milwaukee the greatest impact is in lower- to middle-income neighborhoods. Three out of every four of these absentee landlord properties are on the north and west sides.

Why buy in Milwaukee?

Cheap property combined with tenants willing to pay rent that is high enough for the owners to quickly cover the cost of their purchase and then some.

Highgrove Holdings Management Inc. boasts on its web page that its Milwaukee properties “provide tremendous cash flow of 12%-18% returns annually."

The southern California company, which has about 130 homes in its rapidly growing Milwaukee portfolio, added that "each property generates a gross annualized return rate of just over 20% and in some cases have exceeded 30%."

"What we're seeing here are people from the coasts and even Chicago coming in," said Alex Segal, a Realtor at Re/Max Lakeside, who represented the seller in the 2017 acquisition of $4.55 million worth of Milwaukee homes by a California company called HVL97-Mke-2017 Iceman LLC. "The cost of housing is a lot less here and the rents are good. The rents make it work."

Cheap property and the demand for affordable rental homes brought a pair of former Silicon Valley execs to Milwaukee in 2017 to buy the properties being sold by Segal's client.

Jonathan Kibera and Thomas Fallows, his Harvard classmate and rowing buddy, created HVL97-Mke-2017 Iceman LLC in 2017. The company paid $4.55 million to buy 56 properties on Halloween Day 2017 in the deal involving Segal, according to deeds filed in the Milwaukee County Register of Deeds.

The company, along with SFR3, its sister company, now owns about 95 single-family rental homes in Milwaukee. The HVL97 name is apparently a reference to Harvard University Lightweight Rowing.

Kibera had worked for Google and his partner was at Uber.

The Milwaukee deal proved to be the launching pad for the pair's fast-growing single-family home rental business. SFR3 now owns about 4,000 properties in at least two dozen metro areas and hopes to own more than $2.5 billion worth of properties by 2024, according to the company's web page. Since 2018 SFR3 has filed to raise $130 million through the sale of securities, according to filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

The initial Milwaukee purchase "was an amazing opportunity," because of the low property costs, Kibera said, echoing the rationale voiced by other large absentee landlords. "We're not real estate guys, we're tech guys."

'The fabric of our neighborhoods'

Corporate America began buying up rental homes after the recession of 2008, when millions of foreclosed homes hit the market.

"Post Great Recession ... there was a lot of available inventory — a lot of supply — and few buyers of existing homes," said David Howard, executive director of the National Rental Home Council, an industry trade group founded just seven years ago. "The industry is still very much in the early innings."

So far, the single-family rental industry — a term that didn't exist 10 years ago — accounts for a small percentage of the estimated 23 million single-family rental homes nationwide, the trade group said. But the share is growing as corporations smell the potential for hefty profits.

Some giant players have already emerged, such as Invitation Homes, which has about 80,000 rental homes nationally.

"You will never go broke (renting out) affordable housing," Kibera said. "I don’t see affordable housing going anywhere but up."

There were 106,903 owner-occupied homes in Milwaukee in 2010, according to the US Census Bureau. By 2019, that figure had fallen to 95,247, a decrease of nearly 11%.

Meanwhile, the number of renters rose 8.5%, going from 123,300 to 134,839 during the same period.

The quality of the properties owned by distant landlords varies, said Daren Blomquist, vice president for market economics at Auction.com, an online marketplace for distressed properties.

"Some of these folks do take pride" and hire good local property managers, Blomquist said. Still, "out-of-state investors have got a somewhat justifiable bad rap because some do not take care of their properties."

Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett — who usually jumps at the chance to talk about the city's quality of life — declined to be interviewed for this story.

But Milwaukee Common Council President Cavalier Johnson has been watching with dismay as absentee landlords, some living as far as 2,000 miles from their profit generators, snap up Milwaukee homes.

"Sometimes they buy these homes sight unseen. Stick a body in there, jack up the rent and use it as cash cow," Johnson said. "They're disconnected absentee landlords ... they really don't care about the fabric of our neighborhoods."

Further, the Lubar Center determined that renters often pay more in monthly rent than they would pay on a mortgage if they owned their homes.

The median assessed value of the nearly 1,000 houses owned by the nine largest out-of-state landlords is $61,500, according to the Lubar Center analysis.

For contrast, at least four of the nine largest out-of-state Milwaukee single-family home landlords live in houses valued at more than $1 million, the Journal Sentinel found. They are on both coasts.

Kibera lives in a Mill Valley, Calif., home assessed at more than $5.2 million. The median assessed value of the 95 Milwaukee rental homes owned by his companies was $89,700 last year, according to the Lubar Center analysis.

Kibera contended he still can relate to his firm's rental homes tenants.

"I grew up in New York City," Kibera said. "I know what the other side of the tracks look like."

But local officials — and national housing experts — say neighborhoods and cities can lose something beyond money when renting goes from a mom-and-pop operation to a distant corporate money-making machine.

"It’s a no-brainer if you're sitting in Silicon Valley and your only interest is in making money," said Aaron Glantz, author of "Homewreckers," a 2019 book that chronicled the initial growth of the single-family home rental industry. "Suddenly you have an ultimate absentee landlord who knows nothing about the community, and the tenants have no possibility of talking to their landlords."

Quick evictions, code violations

At a time when housing instability — and evictions specifically — are a crisis locally and nationally, the new breed of out-of-staters are more aggressive than most landlords, the Lubar Center found.

Milwaukee-based landlords file an average of 8.6 eviction suits per 100 units. Seven of the nine largest out-of-staters exceeded that rate, with four of those evicting at a rate of at least 24 annually per 100 units, the Lubar Center found.

The nine largest absentee landlords filed 821 evictions from 2016 through last year, according data compiled by the Medical College of Wisconsin.

"This is not for the faint of heart in these neighborhoods," said David Tomblin, founder and chief executive officer at Highgrove Holdings in Torrance, Calif. "You need to know what you're doing, and you have to follow very strict policies on your rental collections."

He said his company works with cash-strapped tenants in seeking government rent aid.

Highgrove entities, including Residential Properties Resource funds, have filed 97 evictions since 2018 for a rate of 24.4 per 100 units, according to the Lubar Center. Tomblin said many of the evictions were of tenants it inherited.

The absentee landlords also were cited for violating building codes far more often than their local counterparts.

From the fall of 2016 through 2020, Milwaukee landlords have been cited for an annual average of 58.2 building code violations per 100 units. Six of the nine largest out-of-state landlords exceeded that rate, according to the Lubar Center study.

“It’s a cause for concern, certainly,” said Erica R. Roberts, commissioner of the Department of Neighborhood Services, who acknowledged she was unaware of the rate of code violations among the large absentee landlords.

Houston-based Milwaukee Capital Properties LLC and its sister company, SCV Ventures LLC, have the highest rate of evictions and the highest rate of building code violations among the nine largest absentee landlords in the Lubar Center study.

Milwaukee Capital owes $186,570 in back property taxes — plus penalties and interest — as of Feb. 5, according to city records. The two companies also owe the city about $6,500 in municipal court fines.

The companies are owned by Sergio Pejoves, a Peruvian native who came to America in 1999 and moved to Houston around 2006. Shortly afterward he began "acquiring distressed real estate to renovate and resell," according to the website for South Florida Flippers, one of about a half-dozen companies linked to him. Now based in Palm Beach, Fla., Pejoves owns more than 276 rental properties in two markets, according to his LinkedIn page.

Pejoves blamed many of his Milwaukee woes on his former property manager, adding he hopes to soon sell the 115 homes his LLCs own in Milwaukee, getting out of this market.

However, the former manager, Milwaukee attorney Patricia Morrow, said problems were caused by Pejoves' refusal to pay for needed maintenance and repairs. She voiced similar complaints to city building inspectors, records show.

Pejoves was interviewed by the Journal Sentinel in March but ended the call because he said his wife was calling him. He has not returned repeated phone calls since then.

"Being an out-of-state investor is not easy," Pejoves said. "If you don’t have your eyes on your business it becomes more challenging."

The toll on tenants in Milwaukee is another matter.

Kenya Tanner thought she had a local landlord when she rented a home on West Garfield Avenue from one of Pejoves' companies, SCV Ventures LLC.

She didn't know that SCV and its sister company have been hit with 80 orders issued by the Department of Neighborhood Services since 2016. The building inspectors cited the firms with more than 700 building code violations, almost all of which have been abated, dismissed or otherwise resolved, records show.

On an annualized basis, Milwaukee Capital/SCV have been cited for 323 code violations per 100 properties, or 5.5 times the average city rate of 58.2, according to the Lubar Center analysis.

“I wanted somebody here that I could deal with personally if I had a problem,” Tanner said. "When I Googled SCV it didn’t come up as a rental company. I’m like, huh, what is this, who is this?"

Tanner's house had a mouse infestation, a door that let air in, and poor heating. “We were freezing cold,” she said.

Tanner wanted to contact the landlord, but Morrow said that was out of the question.

"We were not allowed to give tenants his number," Morrow said.

Going where nobody else wants to go

Highgrove Holdings — the Torrance, Calif., firm — tries to acquire properties in clusters and then quickly renovate the homes, installing new windows, doors and major appliances.

"We don't provide a Cadillac, but we do provide a high-end Chevrolet," said Tomblin, the CEO.

The cost of purchase and renovations of a Highgrove Home is $35,000, the company said on its website, though the company is increasing the amount it will spend to $75,000.

The company does not shy away from low-income, high-crime areas and will quickly evict tenants who are openly dealing drugs or are involved in other illegal activities, said Johnny Davis, a local property manager.

"We'll go in the areas where nobody else wants to go," Tomblin said.

Part of the reason is likely that the investment cost is so low. The company's plan in Milwaukee is "to seek out and acquire properties in the area at discounted prices up to and in some cases exceeding 50% off of fair market value," its website boasted. Indeed, the median assessed value of Highgrove Milwaukee properties was $32,600 last year, according to the Lubar Center study.

Highgrove has acquired about 135 Milwaukee homes and is in the process of buying another 71, said Trey Barton, a Highgrove vice president. Tomblin said it plans to buy another 300 to 400 properties this year and eventually have 1,100 Milwaukee rental homes in its portfolio.

Davis last month showed off a recently renovated Highgrove home on the 3200 block of Buffum Street, pointing out the new appliances and windows and the remodeled kitchen and bathrooms.

There is a catch. Existing tenants must move out for the house to get a complete renovation. The company will freeze the rent for those who opt to stay and does routine or emergency maintenance and make repairs as needed.

But the major rehab work, such as new windows and appliances will wait until the tenant moves out, Tomblin said.

For example, Sylvester Norwood lives in a century-old Highgrove house across the street from the remodeled home Davis showed. In the winter, Norwood covers his windows with plastic in a futile attempt to keep the cold out of the house.

"They said the only way they'll fix it is if I leave," said Norwood, 78. He has lived in the house for about seven years and pays $625 a month for rent.

He said he lives in the home with his adult son and he has no plans to move "as long as I don't have any problems." As he spoke, Norwood stood in his kitchen, under a strip of peeling paint or plaster.

'I've never been to Milwaukee'

Liqun Schapiro of Rancho Cucamonga, Calif., is not a happy landlord.

Schapiro said that she and her Peachmore LLC bought more than 30 Milwaukee properties after she had a cash windfall from the sale of some condominiums.

"I searched nationwide to see where to park my money," Schapiro said. Milwaukee rental properties came up at the top of the list.

"I've never been in Milwaukee; I never saw the properties," said Schapiro, who lives in a home assessed at nearly $800,000. "Even up to now I've never been to Milwaukee."

Schapiro complained about property managers she hired and city inspectors who cited her properties with 231 building code violations — most of which have been resolved. Schapiro and her husband, Alan, have also been fined more than $3,000 by municipal courts.

She said many tenants stopped paying rent during the pandemic because they know there is a federal ban on evictions. Yet, she said, she is required to pay water bills and other expenses.

Last year, she voiced some of her complaints to a building inspector and objected to being told to make repairs after a tenant have moved out.

"Owner wants to sell the property with violations still attached to property and does not want to fix the property," Nastacia Smith, a DNS inspector wrote in a September 2020 inspector report. "Does not think that she should have to fix the property if no one is living there."

Schapiro said she is in the process of selling her Milwaukee portfolio to Highgrove.

"Milwaukee is very business unfriendly for the remote investor," she said. "It's very difficult for the out-of-state investor to be success."

That's hardly the sentiment of other investors.

VineBrook Homes, of Dayton, Ohio, has been the most prolific buyer of Milwaukee single-family homes to rent out. Since 2019, it has bought about 340 properties, including nearly 90 this year. Dana Sprong, the VineBrook founder and managing member, told the Journal Sentinel the company hopes to see that figure grow to 500 to 1,000 homes.

The median assessed value of a VineBrook home in Milwaukee last year was $84,400, according to the Lubar Center analysis.

Nationally, VineBrook had more than 13,000 rental homes in 14 states, largely in the Midwest and South. The company has raised more than $550 million from investors and is in the midst of a $1 billion offering, according to records filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

"We have an undersupply of affordable housing in our country," Sprong said. "I don’t see that swinging rapidly back in favor of higher owner occupancy."

VineBrook expects to continue its focus on cities like Milwaukee. He argued the company is not an absentee landlord because, like some other companies, it has local staff in Milwaukee and other venues.

There have been some bumps in the road for VineBrook.

The city filed judgments against the company for $2,980 in unpaid municipal court fines for building code violations. Consumers have filed about 108 complaints with the Better Business Bureau against the firm.

Unwilling to work with tenants

Bulldog Ridge LLC and two sister companies are based in the Chicago area and own about 175 Milwaukee properties, many in low- and middle-income neighborhoods. The absentee landlord group also include NSBS Group LLC, Atkinson Ventures LLC and Muskego Ventures LLC. Companies in the Bulldog group owe $157,914 in delinquent taxes, as of Feb. 5.

Wisconsin corporate records show that three of the companies are based in a storefront housing Janko Properties, located in a rundown business strip on the border of Oak Park and Cicero, west of Chicago. The sign on the Janko storefront is worn out. The "O" in Janko is faded, so it appears to read "Jank" Properties.

Matt Janko, an owner of Bulldog and its sister companies, is also a landlord in Chicago and is linked to about 15 LLCs in Illinois and Texas. He did not return repeated messages left by phone and one left in person at the Oak Park office.

The Bulldog group of companies have paid Milwaukee Municipal Court fines of more than $25,000.

Elisha Davis twice rented homes owned by companies in the group and had landlord problems each time, she said.

"There were non-stop mice," Davis said about the first place she rented from Muskego Ventures on the 2400 block of Maple Street. "I called for months. I said I have a daughter; I can't live like this."

Her daughter was 1 year old at the time, said Davis, 23.

She said the house also had a window that didn't lock that eventually was used by burglars to break in.

Later she and her family moved into a second home — this one in an apartment building — that was in better shape.

The second rental, this one from NSBS, ended when they fell behind in their rent in 2019.

Davis said she told the property manager that her husband was on a brief layoff and they would pay two months rent when he was back on the job. The offer was refused, she said, adding they moved out but were sued for eviction anyway.

"I tried to do a payment plan, but landlord was rude and hard to communicate with," Davis wrote in her response to the eviction suit.

Davis said they moved out before NSBS filed an eviction action. The eviction was quickly dismissed, and Davis' name was later sealed from the online court record, court records show.

"Large, distant landlords tend to be much less flexible, they tend to come down on you faster and evict," said Alan Mallach, a senior fellow at the Center for Community Progress. "There is something really nice about having a landlord who lives in the neighborhood, so if you have a problem you could say, 'Look, could you give me a couple of days to pay my rent?'"

Since 2016, Milwaukee building inspectors have hit Bulldog companies with 172 orders citing the group with more than 700 violations of the building code. Almost all the violations have been abated, dismissed or otherwise disposed of.

About two years ago supervision of the companies was transferred to Neighborhood Services' special enforcement division, meaning all its cases were assigned to one inspector.

The Bulldog companies have been performing better, said Jason Rusnak, the inspector assigned to oversee the group.

"They get the work done. It may take them some time, they may not initially respond to the tenant right away, but once we get on them, they're pretty quick," Rusnak said. "It would be nice if they would be more responsive (to tenants) but that’s why we're here."

New laws benefit property owners

The influx of absentee landlords can make an inspector's job more difficult especially when the property owner lives more than 1,000 miles away and blows off the inspector.

"It's obvious that’s a lot of draw on the city's resources when you're trying to gain compliance," said Roberts, the DNS commissioner. "You're doing a lot of calls, you're documenting everything … and you do get a bit of the runaround."

That appears to what happened last year when DNS ordered Pejoves' Milwaukee Capital Properties to exterminate the rats in a rental house on West Chambers Street. The landlord was ordered to correct 18 other violations, city records show.

Among other things, Candace Eubanks, the inspector, said repairs were required for the furnace, doors and electrical outlets. She also cited the property for not having ample smoke and carbon monoxide detectors.

Morrow, the property manager, told Eubanks the items she listed were "not a housekeeping problem" but that Pejoves "has not released funds to make repairs," Eubanks wrote in a report last year.

Eubanks wrote that she called the Palm Beach landlord, but it appeared that Pejoves didn't want to be bothered.

"He stated to work with Patricia Morrow. Do not call him. I stated that we contact owners and managers when possible," Eubanks wrote.

In a interview with the Journal Sentinel, Pejoves denied brushing off the inspector.

"I didn’t say that," Pejoves said. "Probably I was in a meeting or something."

Roberts said the time is coming for the city to change how it deals with absentee landlords. However, doing so may be difficult as state lawmakers have handcuffed the city, limiting what it could do to enforce building codes.

Since 2010, the Republican-controlled Wisconsin Legislature enacted scores of changes in state landlord-tenant laws that benefit property owners.

Many of those changes were pushed through the Legislature by Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, and other legislators who moonlight as landlords.

For example, the number of fines the city can impose are capped by state law and the city can no longer require that a landlord provide it with a local contact person.

"Now they could give us their cousin in California" as the contact, Roberts said.

"We might have to look at better approaches," she added. "We're just limited in our resources and the amount of time we can invest in each of these cases."

Andrew Mollica and Erin Caughey of the Journal Sentinel staff contributed to this report.