PHOTO BY ANGELA PETERSON/MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL

PHOTO BY ANGELA PETERSON/MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL

On the morning of May 3, 2002, Alexis Patterson’s stepfather walked her to the corner and a crossing guard guided the 7-year-old across the street toward Hi-Mount Community School in Milwaukee. At the end of the day, she didn’t come home.

A month later and more than a thousand miles away, Elizabeth Smart, 14, went to sleep in her bedroom in Salt Lake City. By the next morning, she was gone.

Within hours, Elizabeth’s disappearance was featured on CNN’s “Larry King Live” and Fox News’ “On the Record with Greta Van Susteren.” It took eight days for Alexis’ story to attract attention outside Milwaukee, with a segment on “America’s Most Wanted.” The next national story on her case aired weeks later.

By the time Elizabeth had been gone two weeks, USA TODAY had published three stories about her disappearance. There were none focused on Alexis.

The law enforcement response also differed. The day after Elizabeth disappeared, police called in the FBI and offered a $250,000 reward. In Milwaukee, the FBI didn’t join Alexis’ case until three days after she vanished. Nineteen days after she was last seen, the sheriff’s office offered a $10,000 reward.

Elizabeth is white. She was found nine months after her abduction. Alexis is Black – and still missing.

Timeline: How the missing child cases of Alexis Patterson and Elizabeth Smart differ

Twenty years ago, as police searched for the two girls, some advocates and experts argued that race was a key factor in how authorities and reporters handled their cases. It marked the first time the national media paid serious attention to such disparities.

Two years later, Black journalist Gwen Ifill gave the phenomenon a name: “missing white woman syndrome.” She coined the term after the disappearance of Laci Peterson, a pregnant California woman whose husband was later convicted of killing her. It played out again in 2005, when Natalee Holloway vanished on a class trip to Aruba.

Over the past eight months, the case of Gabby Petito, who disappeared on a road trip with her fiance and was later found dead, has once again brought the issue to the forefront of the public consciousness.

The fact that missing Black people command less media attention than whites has been well documented by academic researchers. Their studies have repeatedly found that cases of missing Black people, children and adults alike, are covered less often than whites and their stories don’t travel as widely through the nation’s newsrooms.

There is little empirical evidence that explains why.

A leading theory faults the lack of racial diversity in newsrooms and media ownership. Another blames the socioeconomic status of Black victims. Because missing Black children often come from high-crime, low-income neighborhoods, the reasoning goes, their families have less influence with law enforcement and fewer financial resources to devote to publicity campaigns.

The way police categorize a disappearance also plays an important role. Cases of suspected abduction, like Elizabeth’s, garner more attention from cops and reporters than children considered runaways by police, as Alexis initially was.

In new research yet to be published, Syracuse University Professor Carol Liebler found that law enforcement officers are the most prominent sources in 87% of news stories about missing children.

“My own thought is that police contribute to the problem by setting the news agenda through what cases they share with media,” she said in an email.

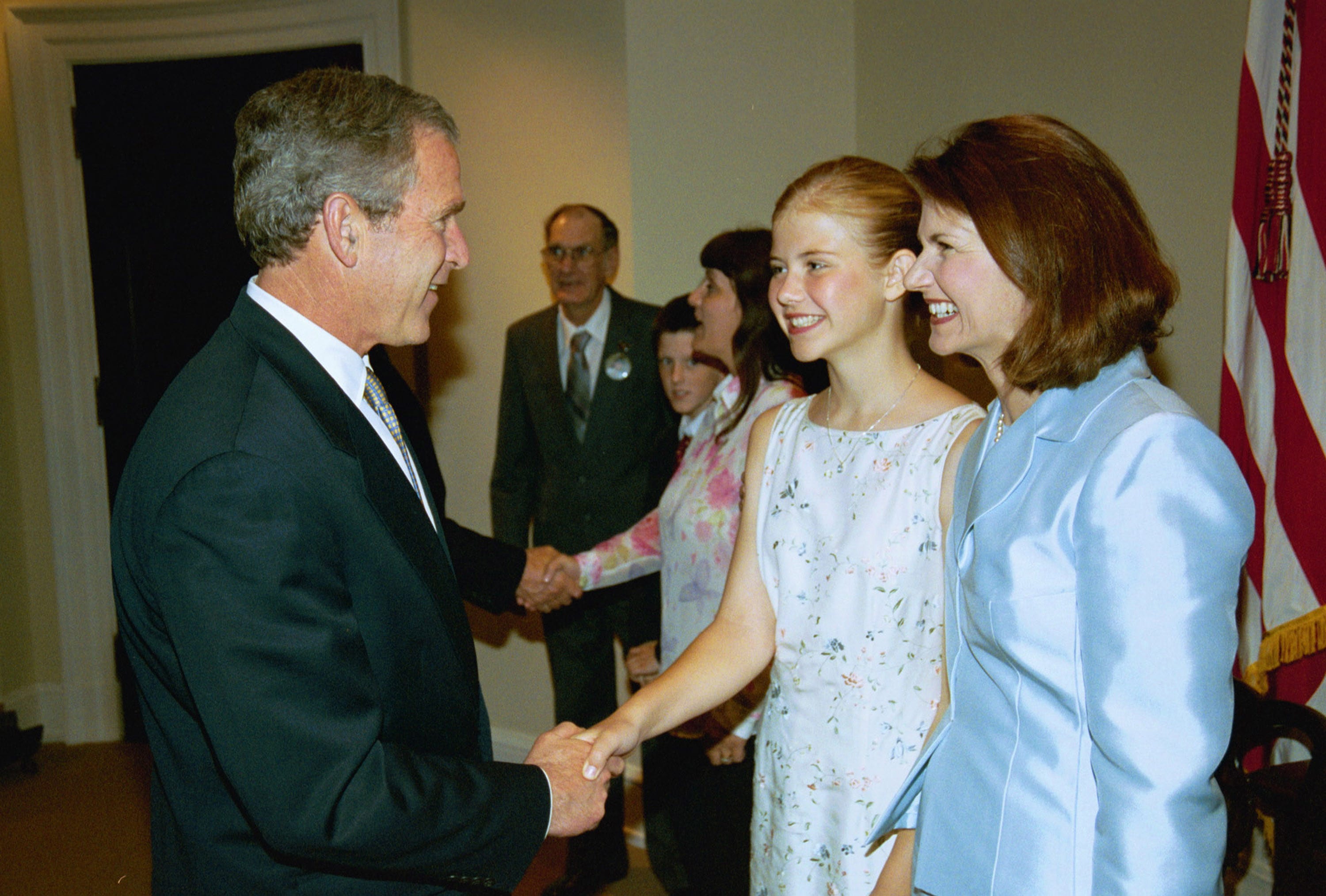

Smart, now an advocate for missing children, acknowledged after Petito’s disappearance how problematic it is that the cases of missing white people get more attention than missing people of color.

Smart, who was unavailable for an interview with USA TODAY while taking time away with her family, made the comments last year on the Facebook Live series Red Table Talk.

“When I think of all of these other victims, I feel like they still deserve, just every bit as much, to be found,” she said. “I don’t think there’s anyone … who is any less worthy than anybody else, myself included, to come home.”

In the coming months, USA TODAY Network reporters will embark on a national project to compile data and public records that expose why these disparities in police response and news coverage of missing children occur and how they can be addressed. In addition to race, we will examine other factors that may explain the discrepancies, including families’ incomes, whether they live in urban or rural areas and whether they have had past contact with police.

We need your help. If you know of missing children of color in your community or have experienced these disparities firsthand as a parent, friend or law enforcement officer, we want to hear from you.

Based on your tips and our own research, reporters around the country will tell the stories of missing children who have yet to be found. Children like Alexis Patterson.

‘My baby never made it’

The distance from Hi-Mount Elementary to the Pattersons’ front door was just 242 steps. Alexis always got home from school around 2:50 p.m. When she hadn’t arrived by 2:55 on that Friday in May 2002, her mother, Ayanna Patterson, began to worry. At 3, Patterson ran to the school in a panic.

“That’s when I found out that my baby never made it,” Patterson told USA TODAY. “She never made it to school.”

None of the teachers had seen Alexis that day, but no one had notified her parents of her absence even though the straight-A student prided herself on perfect attendance. Patterson checked with her grandmother, who lived nearby, but she hadn’t seen the girl either.

So Patterson called the police.

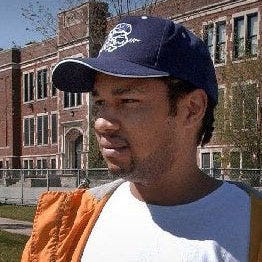

Within a day, the Milwaukee Police Department set up a mobile command post, a trailer packed with communications equipment, at a park near Alexis’ home, according to news coverage at the time. Three days later, Milwaukee Police Chief Arthur Jones told reporters he believed Alexis had run away.

That theory stemmed from an argument she had with her mother the morning she disappeared. The previous day, Patterson had taken Alexis to the store, where she picked out some cupcakes to share with her classmates. In the morning, Patterson realized Alexis hadn’t finished her homework, so she wouldn’t let her bring the treats.

Despite investigators’ belief that Alexis was so angry she skipped school, Milwaukee police acted with extreme urgency, said Chief Jeffrey Norman, who was a detective back then.

“There was a frenzied approach of, ‘There’s someone missing in our community, a young one, and we’re going to put in all the effort, the work, hold no stops,’” he said in an interview last week. “I know that the department took it very seriously. We all paid attention. We were all expected to have some type of role.”

If Alexis went missing today, Norman said, police would issue an Amber Alert because of her age. The alerts, which are disseminated to the public and the press via cellphones, billboards, news organizations and social media, include children’s photos, descriptions and information about when and where they were last seen.

A federal law designed to help states implement Amber Alerts nationwide was passed in 2003 – the year after Alexis and Elizabeth vanished – and all 50 states had set them up by 2005. As of the end of last year, more than 1,000 missing children had been recovered as a result of the alerts.

In 2002, Wisconsin had not yet adopted Amber Alerts. Although it was then called a Rachael Alert, Utah had already set up its system – another key difference between Alexis’ case and Elizabeth’s. As a result, information about Elizabeth’s abduction was disseminated widely within hours. The Deseret News ran a story the following day.

In Milwaukee, the first story about Alexis was published in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel on Sunday, two days after she disappeared.

Years of anger and despair

In any missing child case, it is standard procedure for police to start with those closest to the child, including the parents. Both Alexis’ parents and Elizabeth’s were questioned by law enforcement in the early days of their daughters’ disappearances.

“I know that can be a little disheartening or unnerving,” said Norman, the current Milwaukee chief. “We have seen, unfortunately, (sometimes) those who are entrusted with the welfare of their own children … have broken that trust. ... Being an investigator and being objective, you look at all angles.”

Investigators also used polygraph tests in both cases. Although the results are generally not admissible in court in either state, some members of law enforcement – then and now – consider polygraphs useful tools in solving crimes. News reports from the time say several of Elizabeth’s relatives took polygraphs, but there was no mention of the results.

In Milwaukee, law enforcement sources leaked information to the media, saying Alexis’ mother had passed a polygraph, but her stepfather, LaRon Bourgeois, had failed. He angrily denied the reports.

“If I would not have passed, then I wouldn’t be standing here,” he told a local reporter at the time.

Norman would not say whether the earlier news report was accurate.

For months after Alexis disappeared, Patterson almost never left the house. She couldn’t sleep. A song by Black gospel singer Yolanda Adams played on repeat: There is no pain Jesus can’t feel, no hurt he cannot heal, for all things work according to his perfect will. No matter what you’re going through, remember God is using you, for the battle is not yours, it’s the Lord’s.

Friends and relatives stayed around the clock to help Patterson care for her infant daughter, born six months before Alexis vanished.

In the days and weeks that followed, hundreds of tips rolled in. Police traveled to Chicago, Louisiana, Texas and Atlanta in hopes that one of them would pan out, but none did.

Patterson spent the next few years angry. She and Bourgeois split up. Nearly every conversation she had with police about Alexis’ case ended in a shouting match.

Everything changed when a reporter knocked on her door in 2016.

An unresolved case

By then, 14 years had passed. The reporter showed Patterson a photo of a woman named Lisa who lived in Bryan, Ohio, nearly 300 miles from Milwaukee. The resemblance to an age-progressed photo of Alexis posted by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children was uncanny.

“I know that’s my child,” Patterson told USA TODAY in April. “I’m not afraid of nothing now that I know my baby’s safe, and I know my baby’s alive.”

Police records say otherwise. They show an officer in Ohio swabbed Lisa’s cheek in front of witnesses, then sent the sample to Milwaukee police via FedEx. From there, scientists at Wisconsin’s state crime lab sequenced it and compared it to Alexis’ DNA profile. Milwaukee police told Patterson it didn’t match – but she doesn’t believe them.

Patterson believes having strangers collect the sample and ship it left open the possibility that someone could have tampered with it. She can’t understand why Milwaukee police didn’t travel to Ohio to collect Lisa’s DNA.

Patterson said as much when she spoke with a new Milwaukee cold case detective recently – only the second or third conversation she has had with him since he took over the case more than a year ago.

His response, according to a recording Patterson made of the conversation, was to accuse her, again, of being involved in Alexis’ disappearance.

“If I went to Ohio and swabbed Lisa’s mouth myself … if I do that, if I bring it back here and it’s not a match … will you tell me what really happened?” he asked Patterson.

Recalling the phone call, she shook her head.

“I poured out my heart to this man, and that’s what he says?” she said. “I told him everything. I told him the truth, and he says that?”

Norman, the police chief, acknowledged that probably wasn’t the best way to gain Patterson’s trust.

“I always hope that … we as a department be as professional and honest and forthright as possible,” he said. “But we have a lot of work to do.”

When Patterson tried to get the FBI involved in verifying the identity of the Ohio woman, she received a similar response. The agent told Patterson she had failed her first polygraph and implied they wouldn’t help unless she took another one, according to a recording Patterson made of that phone call.

If Patterson passed “with flying colors, then nobody has a second thought about doing whatever we need to do,” the agent told her. “It’s a win-win for you. Because if you pass it, then you can tell anybody you want, ‘Look, I passed this polygraph.’ If you don’t, you don’t have to tell anybody. There’s no court case that you’d be wrapped up in.”

The agent added that supervisors at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children would confirm a polygraph is necessary.

“They would tell you, in today’s environment,” she said, “this is one of the things that’s automatically done. Polygraphs.”

That isn’t true. The center’s “Long-term Missing Guide for Law Enforcement” discusses reviewing past polygraph results but not administering new tests.

Patterson said she wouldn’t take a second test unless the FBI showed her the report of her first one, and they refused.

“I feel like it’s because of me being African American,” Patterson said. “I didn’t finish high school. I’m from the 'hood. They probably did my background. You know, my mom was on drugs, my daddy wasn’t around. They wouldn’t have never treated me this way if I was white.”

I feel like it’s because of me being African American. They wouldn’t have never treated me this way if I was white.

An FBI spokesman declined to comment. But Norman confirmed that police still have not ruled out the possibility that Alexis’ mother and stepfather may have had something to do with her disappearance.

“To my understanding, there has not been any conclusive evidence clearing … anyone in this particular situation,” Norman said. “We are being as professional and responsible as possible. Until told otherwise, we have to keep all those possibilities open.”

Some investigators have continued to focus on Alexis’ family because they didn’t trust her stepfather, who had driven the getaway car after a 1994 bank robbery in which a suburban police officer was killed, according to according to retired Milwaukee Police Detective Steve Spingola, who was in charge of Alexis' case in the beginning. Bourgeois received immunity to testify against the suspected shooter.

Bourgeois, who denied having anything to do with Alexis' disappearance, died of a probable drug overdose in 2021. If he was involved, Patterson says, he never told her.

Keeping hope alive

Every year since 2012, longtime Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett has recognized May 3 as “Alexis Patterson Forget Me Not Day.” Before he left office to become the U.S. ambassador to Luxembourg late last year, Barrett signed the proclamation for 2022.

Each certificate was proudly displayed, alongside a poster-sized photos of Alexis, at an event Sunday in Milwaukee marking the 20th anniversary of her disappearance.

About 100 people attended the gathering, which Patterson called an “awakening,” to join in prayer, poetry, music and a banquet prepared by Patterson and her family.

On a stage draped in lavender and purple – Alexis’ favorite colors – teachers shared their memories of a girl who as a preschooler called her drawings “homework” and learned to read before she started first grade.

“She always had a beautiful smile for everyone,” said former Head Start teacher Benedicta Graves. “Everybody always wanted to sit next to her.”

In addition to celebrating those who have stood by her for two decades, Patterson also spoke her truth, loudly and sometimes through tears.

“Alexis is alive,” she said. “And I ain’t giving up.”

Anyone with information about Alexis Patterson is asked to contact Milwaukee police at 414-935-7360. To remain anonymous, contact Crime Stoppers at 414-224-TIPS or use the P3 Tips app.

Contributing: Rachel Looker

Contact Gina Barton on Signal at 262-757-8640 or at gbarton@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter at @writerbarton.